I can’t remember exactly when I first crossed paths with Dr. Lee Jang-joo, but in terms of years, it’s probably been close to a decade. As a board member of the Game Culture Foundation, an adjunct professor at Kyonggi University’s Graduate School of Public Administration, Welfare & Counseling, and a key public voice in the game industry, Dr. Lee has remained — then and now — an observer of the game industry and an advisor standing beside it.

Yet there are not many people who truly know him well. Even among gamers and those working in the game industry, unless you are someone deeply interested in the field as a whole, it’s rare to find someone who is familiar with Dr. Lee.

But the work he has done has never been trivial — and that remains true today, even though what began as institutional research has now become something he pursues independently, without outside support. From his own position, Dr. Lee has always done much for the game industry — and he continues to do so.

So when it came time to select the “Person of the Year” at the 2025 Inven Game Awards, there was, in truth, little disagreement. Everyone already knew what he had done.

And perhaps now is the right moment to share that story more widely — the path he has walked, and why he was chosen as a figure who represents 2025.

▲ Dr. Lee Jang-joo, photographed in his research office

How a 31-Year-Old Psychologist Began Looking Into Games

In 2002 — the year South Korea turned red with World Cup fever — Dr. Lee earned his PhD in cultural social psychology at the young age of 31. The subject he was most interested in at the time was not games, but generational change. Why is it that two thousand years ago, and even now, older generations say, “Kids these days have no manners”?

There is, of course, a shared emotional base that members of the same culture or ethnicity hold in common — but that alone cannot explain generational differences or conflict.

▲ Dr. Lee Jang-joo, who earned his doctorate relatively early in life

He focused on how personality formation follows changes in environment and tools. A 15-year-old child, he observed, often feels greater affinity with another 15-year-old abroad who shares similar culture and media experiences — rather than with their own parents. In this sense, social change produces generational differences, and those differences become the source of generational conflict.

And 2002 was an era in which computers and the internet were reshaping human life day by day. Rather than asking “Why are young people different?”, he asked: “How do generational differences come to exist?” From there, he realized that computers, the internet, and game culture were emerging as the current flowing beneath a new generation.

In reality, many aspects of daily life had already changed. Unlike in the past — when work and leisure were completely separated in terms of time and space — people now worked on computers and spent their leisure time through computers as well. Technological progress created more idle time, which led to the establishment of the concept of the five-day workweek.

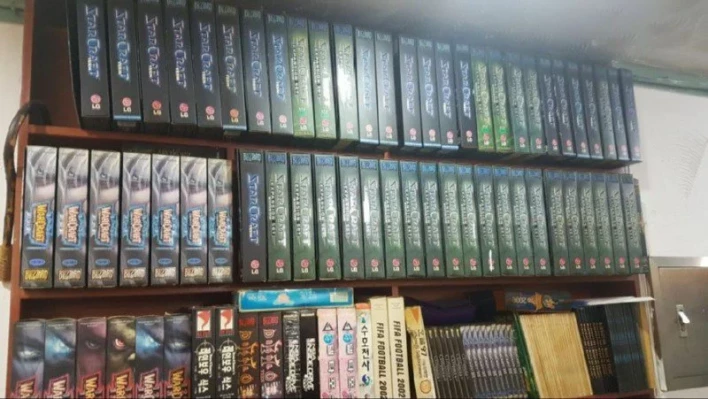

▲ Those who remember this era will recall it vividly — the period when the game market exploded in scale

To this, the concept of leisure studies was added. As an academic field centered on play culture, leisure studies had already been researched for quite some time. Simply put, it is the study of “how people play.” At that time, the internet and video games were emerging as major new research trends within leisure studies.

Meanwhile, the government had not yet figured out how to position “games” within policy or social discourse. It was around the mid-2000s that Dr. Lee began forming his first meaningful connections with the game industry.

As an Observer and Advisor to eSports

Dr. Lee first stepped into the game industry in the mid-2000s, when the government began to examine eSports. The government was still struggling with how to frame eSports, and a request for participation was sent to the leisure studies association to which Dr. Lee belonged. As a young PhD with strong interest in games, he volunteered to join the forum — examining eSports from an academic perspective and analyzing the tangible and intangible value the industry created.

During this process, he played a central role in establishing and operating an eSports research center at Myongji University, carrying out various research projects. He closely observed the structure of the early eSports ecosystem — players, teams, broadcasting, operations, and investment — while identifying existing problems and considering how improvements might be made. Because most early eSports tournaments were small-scale events without major capital, Dr. Lee and other early stakeholders believed that inflows of large capital were essential to expand the scene.

▲ In the very early days, it was unclear where to even begin fixing things in the eSports industry

And just as he predicted, large capital began to enter eSports in the mid-2000s. Telecommunications companies created teams bearing their own names. Corporations such as Samsung, CJ, and Woongjin/ Hwaseung operated professional teams. Even the Air Force created its own “Air Force Game Team,” becoming a beacon of hope for players preparing for military service.

But once this happened, problems arose that even Dr. Lee had not anticipated.

Management of these early professional game teams typically fell under each company’s public relations department — which meant that KPIs were aligned with PR metrics. The more exposure the team generated, the better the PR department performed. As a result, the number of matches increased endlessly.

Contrary to expectations that major capital would stabilize eSports, the scene moved instead toward player overwork and exploitation, producing even worse outcomes.

Looking back on this period, Dr. Lee says he carries a deep sense of debt. Most eSports players were only in their early to mid-20s. They had no choice but to keep competing, even as excessive schedules left them with joint and cartilage injuries. And their future was anything but bright. Younger players were constantly emerging, shortening pro careers, and their post-retirement paths were extremely uncertain.

▲ He recalls that the problems went far beyond individual misconduct — they were structural

Then a match-fixing scandal broke out. The player at the center of the incident was quickly branded the main culprit — but Dr. Lee says that even if it had not been him, a similar case would eventually have occurred. He is not defending the act — but the StarCraft-based eSports ecosystem at the time was fragile in many ways. For an industry to expand, more people must be able to make a living within it — but what Dr. Lee saw was an eSports scene stuck in maintenance mode, advancing only on the sacrifices of its players.

Around this time, Dr. Lee’s voice also began to lose influence. He consistently argued that many of the government’s eSports policies — regional franchise systems, aggressive offline event hosting, and so on — were values suited to 100-year-old traditional sports, and that applying them wholesale to eSports meant abandoning future potential and moving backward.

He warned that excessive fixation on “sportifying eSports” could restrict the unique enjoyment and dynamism of eSports — and excessively shrink one of its defining strengths: not being bound to physical location. His arguments diverged from mainstream policy directions, and over time, his relationship with the eSports field gradually faded.

Opposing the Formal Classification of Gaming Disorder

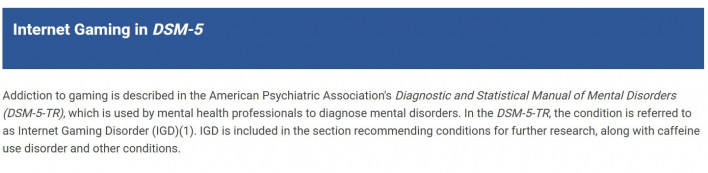

As the 2010s began, Dr. Lee turned his attention to the growing discourse around Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD). The term first appeared in 2013 in the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), published by the American Psychiatric Association — but at the time it was placed in Section III, meaning it required further research and was not yet a formal disorder.

Yet in Korea, public sentiment was already treating gaming addiction as if it were a firmly established phenomenon. Even though academic definitions were incomplete — and the American Psychiatric Association itself stated that more research was necessary — domestic news coverage around 2010 increasingly amplified negative perceptions of games.

▲ Under the DSM-5, Gaming Disorder was categorized — like Caffeine Use Disorder — as a condition requiring further research

During this period, Dr. Lee actively published columns on game culture, working to reshape public perception while also conducting research on gaming over-immersion and related issues. The debate accelerated dramatically in 2019, when the WHO announced ICD-11, formally assigning Gaming Disorder a disease code — triggering discussions over whether Korea should recognize it as a medical disorder as well.

As voices in favor of officially classifying Gaming Disorder gained momentum, Dr. Lee persistently argued that the WHO’s decision lacked sufficient evidence and clear criteria. There was no established definition for how Gaming Disorder should be diagnosed — nor clear proof of what specific and measurable harms it caused. In such a state, he argued, the classification should not be accepted lightly.

From the perspective of someone who had spent half his life studying differences between younger and older generations, the formal adoption of Gaming Disorder felt to him like a narrow, weakly-supported claim — one that risked producing social harm instead.

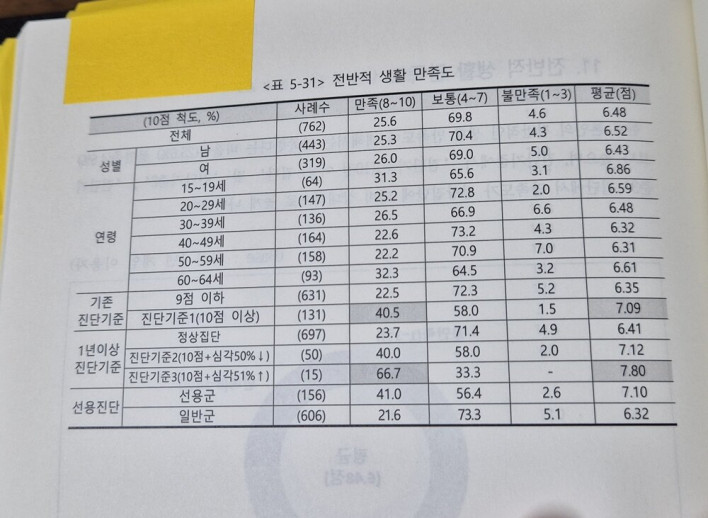

Claims such as “Playing three hours a day means Gaming Disorder,” or “Reducing game time will produce a more productive society,” struck him as unreasonable and unsubstantiated. In fact, in the studies and surveys he conducted to test such assumptions, the only consistent results were that gameplay increased life satisfaction and efficacy.

▲ The research repeatedly showed: the more intensively people played games, the higher their reported life satisfaction

During the height of COVID-19, Dr. Lee shifted focus toward active lectures for parents — recognizing that simple opposition to Gaming Disorder classification had limits. He spoke about how parents could communicate with their children — and how games could function as a tool for communication. He says he continued giving at least one lecture a month during this time, and even now still does so. He also authored the book How to Communicate With Children of the Gaming Generation, which went on to rank second on the bestseller list, following Dr. Oh Eun-young.

Dr. Lee emphasizes that his stance is not “opposition for its own sake,” but rather “verification first.” If a broadly acceptable standard of judgment were established — and if real, demonstrable social harm were clearly proven — he says he would willingly accept Gaming Disorder as a legitimate classification. But in reality, no such research progress has been made, nor has it been clearly proven that games reduce productivity.

For that reason, he continues to insist on the need for research and verification. Having observed the game industry for so long, he felt he could not simply stand by while the field moved toward an irreversible, misguided decision.

▲ Dr. Lee stresses that his stance is not simple “opposition,” but a commitment to thorough verification first

Dr. Lee Jang-joo in 2025

In early 2025, Dr. Lee joined the Democratic Party of Korea’s Game Special Committee. Overlapping with the presidential election season, he participated in developing game-related policy pledges — serving as vice-chair of the first committee and leading the Gaming Disorder Response Subcommittee.

Regardless of political alignment, he believed it was worthwhile if a leading presidential candidate could at least express opposition or cautious reservation toward Gaming Disorder classification. Through this work, he proposed numerous ideas — among them, he says, the most meaningful accomplishment was placing “suspension of Gaming Disorder adoption” as the committee’s first formal policy recommendation.

Then, in October 2025, during an event held in Seongsu-dong, the sitting president declared publicly that “Games are not an addictive substance.” Dr. Lee says that, thanks to this, “time was gained” — but also emphasizes that such political solutions are inherently temporary and can change at any time. They merely postpone a decision; they do not resolve the underlying issue.

▲ At the event where the president declared, “Games are not an addiction,” Dr. Lee explains that this development effectively bought time for verification

For that reason, he is now planning new research to pursue a more fundamental solution. The core of this research is falsifiability. To approach the issue academically, he argues, we must be able to disprove claims — yet at present, there is no falsifying framework, meaning discussions remain vulnerable to arguments in favor of Gaming Disorder classification.

In other words, there is still no systematic way to challenge claims such as “Playing a lot of games causes problems” or “The problem stems from games.”

Dr. Lee’s research now moves beyond the simplistic “addiction / not-addiction” dichotomy — examining what kind of scientific evidence and social conditions should be required to define, maintain, or withdraw Gaming Disorder as a disease code. By analyzing life satisfaction, functional impairment, comorbid conditions, and social stigma together, he aims to distinguish cases where games are truly a causal factor from cases where gaming is merely an expression of other issues such as stress or anxiety — and to propose a policy decision framework based on falsifiability.

If Gaming Disorder solidifies into a disease code without this falsifiability, its effects will extend beyond industry and policy — eventually affecting the daily lives of ordinary gamers. When a diagnosis with vague concepts and definitions is introduced first, even ordinary players who simply enjoy games may be treated as potential patients, or become targets of suspicion and restriction simply because they like games.

Once such stigma and regulation are institutionalized, reversing them becomes extremely difficult. That is why, Dr. Lee stresses, the most rational and publicly defensible approach is to first establish clear, falsifiable criteria — including the conditions under which the diagnosis should be reviewed or revised — and thereby prevent the unfounded medicalization of “Gaming Disorder (gaming addiction).”

In 2025, Dr. Lee’s major activities can be summarized as follows:

| Category | Period | Content | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research | 2025.05–2025.08 | Game Use as Serious Leisure: Exploring the Boundary Between Mental Disorders and Serious Leisure | Principal Investigator / Game Science Research Institute |

| Policy & Public | 2025.02 | Participation in Democratic Party Game Special Committee; Vice-Chair, Gaming Disorder Response Subcommittee | Policy consultation & deliberation |

| Academic / Forum | 2025.02.06 | Impact of Gaming Disorder Medical Coding on the eSports Ecosystem | Presentation at Kyungsung University eSports Research Institute Forum |

| Academic / Forum | 2025.04.28 | Why Oppose the Introduction of Gaming Disorder? | Moderator, Democratic Party Game Special Committee Debate |

| Academic / Forum | 2025.05.16 | Games, Society, Stories | Speaker / Moderator, Democratic Party Game Special Committee |

| Academic / Forum | 2025.08.22 | Serious Leisure and Addiction: Commonalities and Differences | Presentation at the Korean Psychological Association Annual Conference |

| Academic / Forum | 2025.08.26 | The Cultural Psychology of Anxiety and Appeal: Implementing Innovative Content and Key Issues | Presentation at Game Science Forum |

| Academic / Forum | 2025.09.08 | NewsTomato Game Forum (NGF 2025) | Panel Discussion |

| Academic / Forum | 2025.11.13 | Exploring the Boundary Between Gaming Disorder and Serious Leisure | Presentation at Game Culture Symposium |

| Content | 2025 | Participation in production of the game literacy education program “Stories About Games More Interesting Than Games Themselves” | Game Culture Foundation · Game Education Center |

This article was translated from the original that appeared on INVEN.

Sort by:

Comments :0