At the ongoing game developers’ conference devcom 2025 in Cologne, game developer and researcher Yaraslau Kot said that Ukraine’s game industry is finding creative ways to reflect the realities of war. Kot, who has been active in the games industry since 1996, is now a researcher at the European Humanities University.

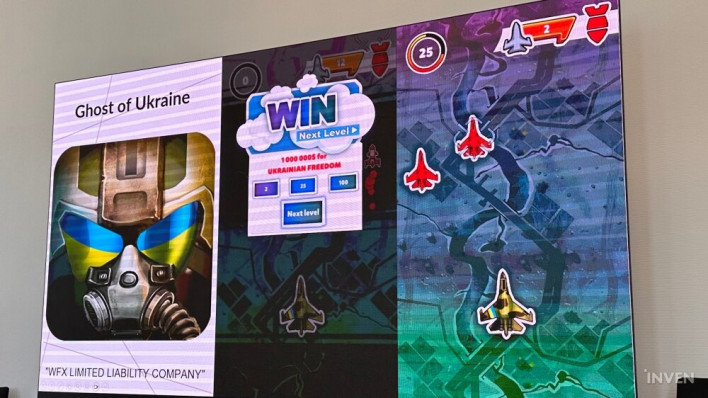

Kot described the war-themed titles produced by Ukrainian developers as “games of war,” stressing that they go well beyond entertainment. He explained that these projects are being created for purposes as varied as therapy, artistic expression, fundraising, communication, countering propaganda, offering moral support, raising awareness, education, and training.

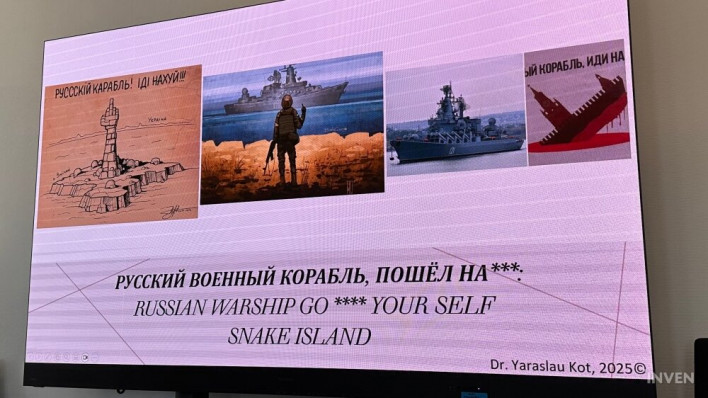

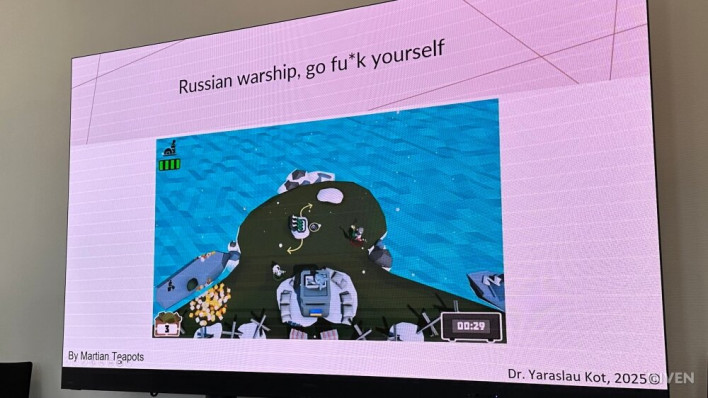

His lecture highlighted a variety of examples that capture both lived experience and symbolic moments from the conflict.

One early success was eBayraktar, a game in which players attack Russian forces. It proved so popular that within a month it was added to Ukraine’s official government portal. Kot noted that it helped people channel their helplessness and anger into something constructive, functioning almost like a psychological release.

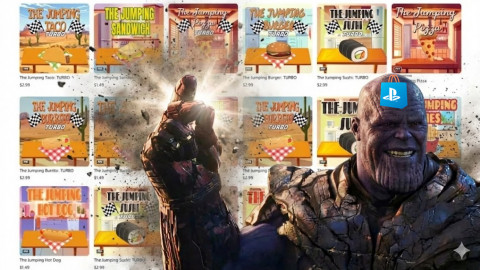

Other projects were created to directly counter Russian propaganda. Zero Losses took aim at Moscow’s insistence early in the invasion that there had been no casualties, by putting the player in the role of a truck driver hauling body bags. Birds Attack 2022 mocked Russia’s claim that Ukraine had been experimenting with birds as biological weapons.

Some specific wartime events even gave rise to subgenres of their own. When footage circulated of Ukrainian farmers towing away Russian tanks with tractors, numerous “Ukrainian tractor” games sprang up.

Another wave of titles was inspired by Chornobaivka, the area where Russian troops repeatedly suffered heavy losses.

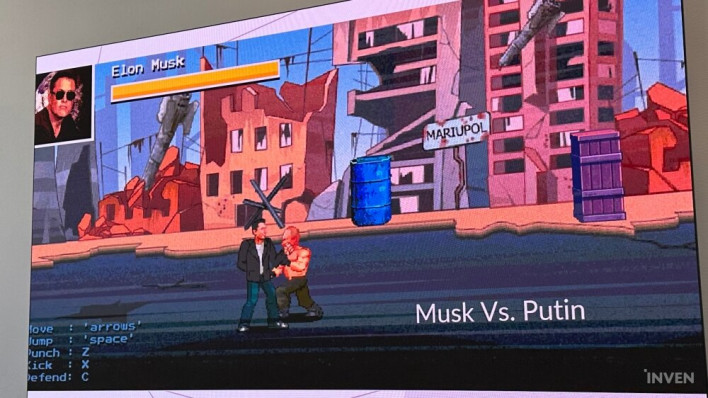

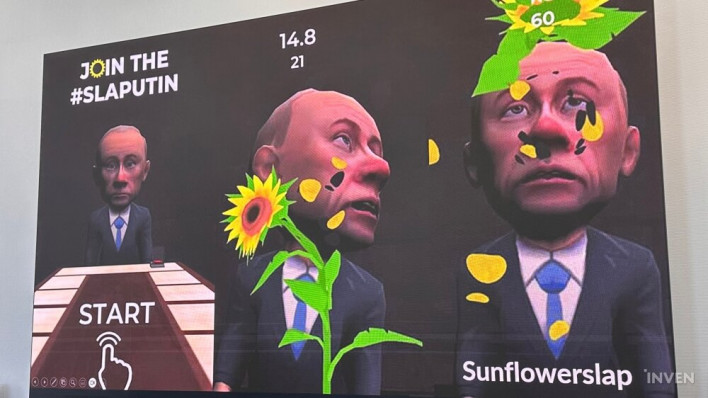

Quirkier examples included Musk vs. Putin, based on Elon Musk’s public challenge to the Russian president to a duel, and a simple but symbolic game in which players slap Putin with a sunflower, Ukraine’s national flower.

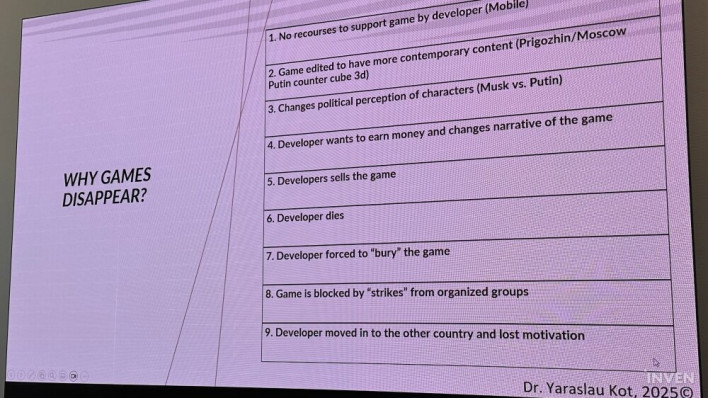

Kot warned that many of these projects are in danger of disappearing because of scarce resources, the deaths of developers, or outside pressure. In many cases, small teams simply do not have the capacity to keep their games updated. Mobile titles are especially at risk, since platform policies change frequently and require maintenance that overstretched developers cannot provide.

He also noted that game content often has to be altered as the battlefield evolves, with earlier versions lost in the process. One example was a title originally called Prigozhin Counter Cube 3D, which was later retitled Moscow Counter Cube 3D after the Wagner leader’s mutiny.

Developers themselves sometimes choose to remove their own work when public perceptions of in-game characters shift. The creator of Musk vs. Putin, for instance, ended the project after deciding they no longer wished to portray Musk positively.

In some cases, developers change their games to make them more neutral, or sell them to other companies, simply to make a living. Many lost their jobs during the war and saw this as their only option. Sadly, there have also been cases where game creators were killed in combat or succumbed to the intense stress of wartime life.

Kot added that developers have faced pressure from the Russian games industry to abandon their projects, and some titles have been taken down after coordinated campaigns of mass reporting online. For those who emigrated, the challenges of adapting to life abroad often led to burnout and a loss of motivation to continue creating.

He stressed that the disappearance of such games represents more than just the closure of services—it also means the loss of important records of the war’s many dimensions.

Despite all this, Kot pointed out that academic interest in these “games of war” is growing. His research helped spur the launch of an annual “Games of War” conference at the University of Gdańsk, which has also introduced a bachelor’s program in historical game design. Meanwhile, the European Historical Game Studies Journal is preparing a special issue dedicated to Ukrainian wartime games.

Kot argued that these projects play a crucial role in documenting the conflict, spreading the truth, and fostering solidarity.

Speaking about everyday life in Ukraine, he observed that underground shelters have become ubiquitous. Even during game conferences, he said, organizers simply move into the shelters when the bombing starts, then continue the event as if nothing had happened.

Asked whether it is worthwhile for game companies to keep their services running during wartime, he was clear that it is. According to Kot, live services can provide comfort to citizens drained by evacuation and fear. He also underlined that keeping the industry alive helps generate tax revenue, which in turn provides the government with resources to support its people. For that reason, he argued, ensuring that businesses keep operating inside the country is a vital effort.

This article was translated from the original that appeared on INVEN.

Sort by:

Comments :0