You have probably heard about non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, at this point.

You may have been told by an eager crypto-investor that they are the future of digital art and collectibles, that they will help preserve digital goods and open a whole new realm of commerce and possibilities in the “metaverse”. On the flip side, you may also have heard that they are bad for the environment, that people are stealing other people’s work and minting it as an NFT, and that companies are using NFTs as a cash grab.

So what is true and what is myth when it comes to this new and controversial technology? We are here to bust some of the most common NFT myths and help you become more informed about NFTs, their uses, and what they are not useful for.

What is an NFT? (but like really)

An NFT, in short, is a “non-fungible token” that confirms the ownership of a product using a token on the blockchain. It can track the purchase history of a product through a “smart contract”, which is a basic set of code tied to a token on Ethereum or another blockchain. The product can be digital or physical, but generally speaking, NFTs are most commonly used to track digital ownership.

Ultimately, the technology is not that complicated, nor is it all that revolutionary. All NFTs really do, in their core essence, is function as a certificate of authenticity. The technology can allow people to take something fungible — like an image, GIF, video file, things that can be saved and reproduced infinitely — and turn it into something that has digital scarcity through “minting” unique, limited tokens tied to those files.

Some have used the term “strict uniqueness” to describe NFTs: a product that is unique and trackable, separate from other products, even if it is a copy of the same thing. Think of your favorite band’s poster, but each print is numbered so you know it is one of a limited run. Or a printed copy of a book, where you have a hard copy that is yours, even if there are millions printed that are just like it. NFTs allow for a digitally simulated version of this.

Busting five NFT myths: What’s real, what's fake, what's complicated?

While in their essence NFTs are relatively simple, there has been a lot of hype around this technology, with many people, including huge influencers and companies, making some very aggressive claims about their potential. While the basic uses for NFTs include tracking the ownership of digital software or establishing a way to create a collection of digital collectibles, there are a lot of myths floating around about this technology and its ability to do things like save art on the blockchain, allow for transfers of in-game skins between different games, and so on.

So here is a quick run down addressing some of the myths and claims going around about NFTs.

Myth 1: NFTs store art on the blockchain for posterity — FAKE

NFTs are not the storing of digital assets on the Blockchain. Enthusiasts have hailed NFTs as preserving art forever on a self-perpetuating machine that will outlast mankind, running itself into the distant future like a crypto mining version of Pixar’s Wall-E, where all that is left at the end of the world is a bunch of Nvidia 3060’s mining Ethereum to keep your art safe.

An NFT, in reality, doesn’t have the ability to store much of any data beyond purchase information on the blockchain. Even purchase history can be difficult for NFTs to track accurately since the token itself won’t automatically know if it's being sold to a new owner or just transferred between wallets. The tokens are separate from the products they represent, just like a certificate of authenticity on a collectible model car isn’t the same thing as the car itself.

So in short, NFTs are an immutable receipt for a purchase, a fancy certificate of authentication, but the actual asset you are buying will exist in some other form. Whether it’s a JPEG, a GIF, or a video, none of it exists on the blockchain. The digital scarcity of NFT projects refers purely to the token, not the actual file.

Wired published an article claiming that NFTs will help us preserve street art on the blockchain by storing it there forever. However, in this situation, it is not the NFT that would preserve street art, even if you minted tokens of images of street art to the blockchain. In their own example — a virtual reality exhibit of street art, digitally scanned and replicated — the NFT is entirely superfluous to that task. A digital scanning technology or a photograph is the actual thing preserving the street art, the NFT has nothing to do with it. Now you could argue NFTs could help street artists get paid, but that is not the same as “preserving” the art forever.

Myth 2: NFTs help artists get paid — TRUE BUT COMPLICATED

One of the bigger talking points about NFTs is the idea that they help artists get paid. This is not a new promise from blockchain creators, projects like Emanate on the EOS blockchain made similar promises about helping music artists get paid through blockchain technology, with mixed results.

However, NFTs have a big issue that really gets in the way of people’s faith that these will become a self-perpetuating norm at some point in the future that artists can rely on for cash flow. There is no copyright authentication in any way for NFTs when they are minted. On top of that, all interactions are anonymous. This makes NFTs a great way to steal art.

The result has been thousands of artists finding their work stolen and minted as NFTs, with another person profiting off of their work instead of them. There have been thousands Deviant Art artists who have fallen victim to this, as well as numerous YouTubers like Stephanie Sterling who have found their YouTube channels inexplicably sold as NFTs, whatever that means. So while Beeple and some other artists have found some success in selling their work as NFTs, many more artists are getting screwed.

Even artists who are minting their own work lose money in many cases. Minting NFTs costs money, or “gas fees” on the blockchain. So you have to sell the NFT for more money than it costs to mint it, meaning some artists are actually losing money if their NFT doesn’t sell for enough.

Another alluring promise of NFTs is the idea that NFTs could allow artists to get royalties on each sale of their minted token. This would be awesome for artists if it happened, but there isn’t a way currently for the token to know the difference between being transferred and being sold, unless it is posted on a marketplace. So sellers could circumnavigate the royalty by doing a private sale. That said, if someone does find a way to create NFT royalties and enforce them automatically, the promise of future royalties is an interesting idea.

In conclusion, NFTs can help artists get paid, and can be a form of legitimate revenue for businesses in some cases. But broadly speaking, the technology does not inherently help people get paid for their work any more than simply selling digital art would, especially at the point where many NFTs are stolen property to begin with, which directly trades off with an artist’s ability to sell their own work.

Myth 3: NFTs will allow you to use digital property across multiple systems or games — FAKE

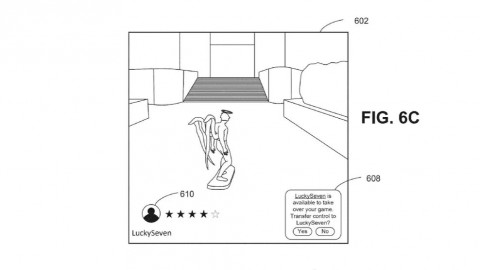

When Mike Shinoda touts that NFTs will let you own a video game skin across multiple games, taking a skin from Halo to Fortnite for example, that is quite false. Similarly, when people tout the future metaverse, where we will all be rocking our NFT cosmetics across various virtual reality spaces, that too is likely false.

Anyone familiar with game development can tell you that the addition of a digital asset into a game can’t just be transferred to another game without significant effort. For NFTs to work across multiple games, the developers would have to collaborate to make their assets compatible with each other. The technology allows it so this could theoretically happen, especially if the developers were owned by the same studio, but this promise has not come to fruition and is not tied in any way to the NFT technology.

Myth 4: NFTs give you the rights to the image — FAKE

NFTs don’t mean anything, legally speaking, and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Last year, a group of crypto investors got together to buy a rare copy of Dune, thinking it would magically grant them the rights to Dune’s IP. In reality, the copyright is still controlled by the owners of the Dune franchise. In a similar fashion, when you buy an NFT of a photograph, unless it came with an explicit licensing agreement, you probably do not have the right to use it or reproduce it. The NFT doesn't really mean anything, copyright-wise.

On top of that, it is possible to mint a token tied to the same product on multiple blockchains. There is nothing stopping you from putting it on several different chains, putting it on Ethereum, Fuse, Bytom, and more. At which point, you have to ask which chain is the authoritative one?

So while many have promised that NFTs will allow us to commercialize all of life, NFTs are actually a kind of clunky, unnecessary extra step to digital products that attempts to create immaterial, finite value, out of otherwise entirely fungible digital goods in many cases. If you want to use something or want the rights to something, you should pay for a licensing agreement instead.

Myth 5: NFTs are inherently bad for the environment — TRUE BUT COMPLICATED

Are NFTs bad for the environment? Well, yes, but not necessarily disproportionately so.

NFTs that exist on proof-of-work blockchains (POW) are arguably pretty bad for the environment because POW blockchains like Bitcoin or Ethereum are very energy-inefficient. They rely on large numbers of computers and servers running the blockchain redundantly all across the world, keeping it decentralized and less likely to go down. This energy inefficiency has been widely criticized in the media, and for good reason.

However, not all blockchains are built the same. There is another type of blockchain called proof-of-stake blockchains (POS), which rely on consensus mechanisms to verify blockchains. This is what Ethereum is moving to, and other blockchains like EOS or Telos have already demonstrated the efficacy of POS blockchains. These chains rely on a comparatively smaller number of validators who stake a certain amount of their tokens to become one of the nodes validating the blockchain, leading to far fewer computers doing redundant work. On networks like EOS, block producers are elected by token holders to represent them.

These networks are much more efficient; their servers come closer to the energy usage of running an MMORPG. So while you could argue that all blockchains are somewhat inefficient, due to the redundancy of information they rely on, some blockchains are not significantly worse than World of Warcraft or a similar MMO. Of course, you can also argue that MMOs aren’t great for the environment either, so the environmental impact of NFTs is a matter of perspective. In many cases they are not significantly worse than online gaming, but in other cases they are.

So NFTs, as a technology, are pretty simple. They are unique tokens that are used as a proof of purchase of a good. They have legitimate uses and they have illegitimate uses, making their impact on the digital landscape ambivalent. With so many huge companies investing into NFTs, it is likely they are here to stay, and hopefully with time they can find a more reasonable, logical place in the market.

-

Aaron is an esports reporter with a background in media, technology, and communication education.

Sort by:

Comments :0